Whilst the idea of co-creating curricula with students-as-partners may seem radical, the origins of the practice are not new to education. Over a century ago, John Dewey critiqued traditional conceptions of formal education and argued for schools where students would have a stronger voice and more agency in their own learning experiences (Dewey, 1916; 1986). Discontent with the way governments were approaching schooling peaked in the 1960s, where formal education was seen as preserving a narrow canon of what was deemed to be valuable knowledge and a range of scholarly works returned to some of Dewey’s ideas (Bovill, 2013).

For example, Brazilian educator Paulo Freire critiqued the ‘banking model’ of education, where students are essentially characterised as empty vessels who passively receive expert knowledge from teachers;

The teacher teaches and the students are taught;

The teacher knows everything and the students know nothing;

The teacher thinks and the students are thought about;

The teacher disciplines and the students are disciplined

(Freire, 1968; 2005)

The students in this banking model of education are understood as ‘marginal’ individuals who deviate from the status quo and require ‘incorporation’ into society via paternalistic pedagogical approaches (Freire, 1968; 2005). At its worst, this form of education promotes an unquestioning acceptance of the way things are, in turn damaging ‘our ability to be human; to hope, dream, love and grow’ (Peters & Mathias, 2018).

However, Freire describes that we can break from the banking model of education, by learning with each other; students and teachers coming together to co-create learning experiences through dialogue, shifting the dynamic of the traditional teacher/student relationship:

Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-students with student-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but who is himself [sic] taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach.

(Freire, 1968; 2005)

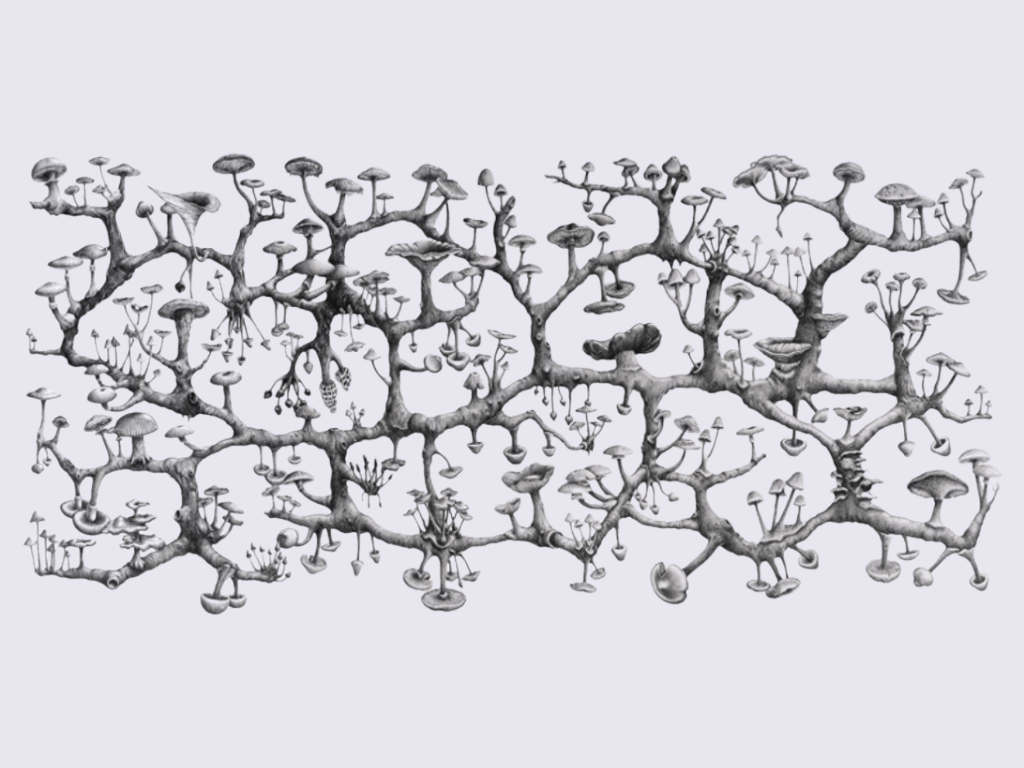

In this alternative model, education is not solely about the transmission of predefined answers, but instead about genuine curiosity and the asking of questions. When such an approach is taken further, a ‘rhizomatic’ development of learning and knowledge can occur; learning and the creation of knowledge developing like the roots of rhizomatic plants, growing in multiple directions and spreading via experimentation and adaptation (Cormier, 2012). We might even reimagine curricula in this sense; not as purely predefined by those with subject matter expertise - as something to be learned, independently verifiable and with a definitive beginning and end goal - but also as negotiated and constructed in real time by those engaged in the learning process (Cormier, 2008).

Whilst such ideas may seem idealistic, we can begin to think pragmatically about adopting co-creative practices by learning from some of the educational institutions and organisations around the world which already engage in various forms of co-creation. There is a broad range of research which illustrates the different ways students can be invited as partners in collaborative curriculum design processes, as consultants, co-researchers, pedagogical co-designers and representatives. Some key areas of co-creative activity include:

- The co-design of courses, where students play an active role in negotiating the scope and plan of learning

- The co-production of learning resources, where students are situated as valuable knowledge producers and curators

- The co-development of assessment, where students are empowered to engage in assessment activities to support themselves and their peers.

Yet, co-creation in this field is complex. Students and staff at any given educational institution or organisation bring different levels of expertise to different processes, and when and where their respective voices should have more influence is dependent on contextual elements such as the relative experience of staff and students, their attitudes, what is being discussed and so on. Whilst all participants in partnership processes should have the opportunity to contribute equally, partnership should not be understood as a ‘false equivalency’; students and staff can and should contribute in different ways (Bovill, 2013; Cook-Sather, Bovill & Felten, 2014).

But why should this kind of co-creation be pursued? Whilst some in the educational sector may be motivated by the works of Freire and similarly progressive educational scholars, there are also further reasons to pursue a co-creative agenda. For example, there are a range of benefits that are consistently found within case studies of where co-creation is pursued. For students, these include deeper understandings of learning and learning processes, increased learning engagement, enhanced motivation and enthusiasm, and stronger student-educator relationships, to name a few (Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017). Moreover, students engaged in co-creation can become more critical and more intellectually engaged and capable of supporting their own and their peers’ learning, as well as that of future students who experience co-created curricula. In turn, this supports students in becoming more responsible for, and active in, their learning. Students shift from passive to active and from merely ‘doing’ to developing a meta-cognitive awareness about what is being done, which can be of value to all involved in the learning process. In particular, research also communicates that co-creation can be of value to educators, re-energising their engagement with - and enjoyment of - their work, leading to transformed thinking and practice regarding teaching.

Moreover, in reference to the ideas of scholars such as Dewey or Freire, partnership practices have significant potential to positively shift power dynamics and to enhance the classroom experience. This can lead to more fruitful and accessible student-educator relationships and remedy the lack of voice and agency associated with traditional transmissive teaching techniques.

There will of course be challenges to moving away from a didactic approach and engaging in partnership and co-creation. Advocates of co-creation often have to navigate institutional norms, practices and structures and are likely to encounter resistance, not only by educational administrators, but also by students, educators, parents and others. Challenging traditional power structures and dynamics can be daunting, especially for those in settings where high stakes testing and the transmission model of teaching are the norm, rather than partnership, shared-inquiry, and co-creation. Yet, research shows that the process of addressing such challenges can be rewarding and critical as spaces of partnership are defined in local contexts and should be accepted as a normal part of the sense-making processes that allows for collective consideration of the complexity of genuine partnerships (Woolmer, 2016).

To support effective lasting partnerships, those engaging in collaboration should seek to foster ‘learning communities’ through a commitment to certain principles. Research shows that partnership is most successful when it is reciprocal, involves students as active participants, and is emphasised by educators as a process of engagement. This can be supported by a commitment to principles such as respect, reciprocity, and shared responsibility, which place educators and students in open discussions, where the inputs of both parties are taken seriously and valued without judgement, and where risk and ownership are shared (Cook-Sather, Bovill and Felten, 2014; Healey, Flint & Harrington, 2014).

In summary, I argue that there is much to be gained from co-creating curricula with students-as-partners, for those engaged in the learning process and beyond. Importantly, reimagining the curriculum as something dynamic, shared, and emergent has the potential to significantly reframe the who, what, why, and how of learning. This is the first step of an act to support students in becoming active, democratic citizens, capable and confident of transforming their world.

You can read the full dissertation article, which includes an exploration of a range of curriculum co-creation case studies, here.

References

Bovill, C., 2013. Students and staff co-creating curricula – a new trend or an old idea we never got around to implementing? In Rust, C., Improving Student Learning through research and scholarship: 20 years of ISL. Oxford: The Oxford Centre for Staff and Educational Development, pp. 96-108.

Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C. and Felten, P., 2014. Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: A guide for faculty. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Cormier, D., 2008. Rhizomatic education: Community as curriculum. Innovate: Journal of online education, 4(5). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234577448_Rhizomatic_Education_Community_as_Curriculum.

Cormier, D., 2012. Embracing Uncertainty - Rhizomatic Learning in Formal Education. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VJIWyiLyBpQ&ab_channel=davecormier [Accessed 14 April 2022].

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F., 1988. A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. London, Athlone Press.

Dewey, J., 1986. Experience and education. The educational forum, 50(3), pp. 241-252. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00131728609335764.

Freire, P., 2005. Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Continuum.

Healey, M., Flint, A., & Harrington, K. 2014. Engagement through partnership: Students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. York: Higher Education Academy.

Mercer-Mapstone, L., Dvorakova, S.L., Matthews, K.E., Abbot, S., Cheng, B., Felten, P., Knorr, K., Marquis, E., Shammas, R. and Swaim, K., 2017. A systematic literature review of students as partners in higher education. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(1), pp. 1-23. Available at: https://mulpress.mcmaster.ca/ijsap/article/view/3119.

Peters, J. and Mathias, L., 2018. Enacting student partnership as though we really mean it: Some Freirean principles for a pedagogy of partnership. International Journal for Students as Partners, 2(2), pp. 53-70. Available at: https://mulpress.mcmaster.ca/ijsap/article/view/3509.

Woolmer, C. 2016. Staff and students co-creating curricula in UK higher education: exploring process and evidencing value. PhD Thesis. University of Glasgow.